Maize: From Mexico to the world

For Mexicans, the “children of corn,” maize is entwined in life, history and tradition. It is not just a crop; it is central to their identity.

Even today, despite political and economic policies that have led Mexico to import one-third of its maize, maize farming continues to be deeply woven into the traditions and culture of rural communities. Furthermore, maize production and pricing are important to both food security and political stability in Mexico.

One of humanity’s greatest agronomic achievements, maize is the most widely produced crop in the world. According to the head of CIMMYT’s maize germplasm bank, senior scientist Denise Costich, there is broad scientific consensus that maize originated in Mexico, which is home to a rich diversity of varieties that has evolved over thousands of years of domestication.

The miracle of maize’s birth is widely debated in science. However, it is agreed that teosinte (a type of grass) is one of its genetic ancestors. What is unique is that maize’s evolution advanced at the hands of farmers. Ancient Mesoamerican farmers realized this genetic mutation of teosinte resembled food and saved seeds from their best cobs to plant the next crop. Through generations of selective breeding based on the varying preferences of farmers and influenced by different climates and geography, maize evolved into a plant species full of diversity.

The term “maize” is derived from the ancient word mahiz from the Taino language (a now extinct Arawakan language) of the indigenous people of pre-Columbian America. Archeological evidence indicates Mexico’s ancient Mayan, Aztec and Olmec civilizations depended on maize as the basis of their diet and was their most revered crop.

As Popol Vuh, the Mayan creation story, goes, the creator deities made the first humans from white maize hidden inside a mountain under an immovable rock. To access this maize seed, a rain deity split open the rock using a bolt of lightning in the form of an axe. This burned some of the maize, creating the other three grain colors, yellow, black and red. The creator deities took the grain and ground it into dough and used it to produce humankind.

Many Mesoamerican legends revolve around maize, and its image appears in the region’s crafts, murals and hieroglyphs. Mayas even prayed to maize gods to ensure lush crops: the tonsured maize god’s head symbolizes a maize cob, with a small crest of hair representing the tassel. The foliated maize god represents a still young, tender, green maize ear.

Maize was the staple food in ancient Mesoamerica and fed both nobles and commoners. They even developed a way of processing it to improve quality. Nixtamalization is the Nahuatl word for steeping and cooking maize in water to which ash or slaked lime (calcium hydroxide) has been added. Nixtamalized maize is more easily ground and has greater nutritional value, for the process makes vitamin B3 more bioavailable and reduces mycotoxins. Nixtamalization is still used today and CIMMYT is currently promoting it in Africa to combat nutrient deficiency.

White hybrid maize (produced through cross pollination) in Mexico has been bred for making tortillas with good industrial quality and taste. However, many Mexicans consider tortillas made from landraces (native maize varieties) to be the gold standard of quality.

“Many farmers, even those growing hybrid maize for sale, still grow small patches of the local maize landrace for home consumption,” noted CIMMYT Landrace Improvement Coordinator Martha Willcox. “However, as people migrate away from farms, and the number of hectares of landraces decrease, the biodiversity of maize suffers.”

Diversity at the heart of Mexican maize

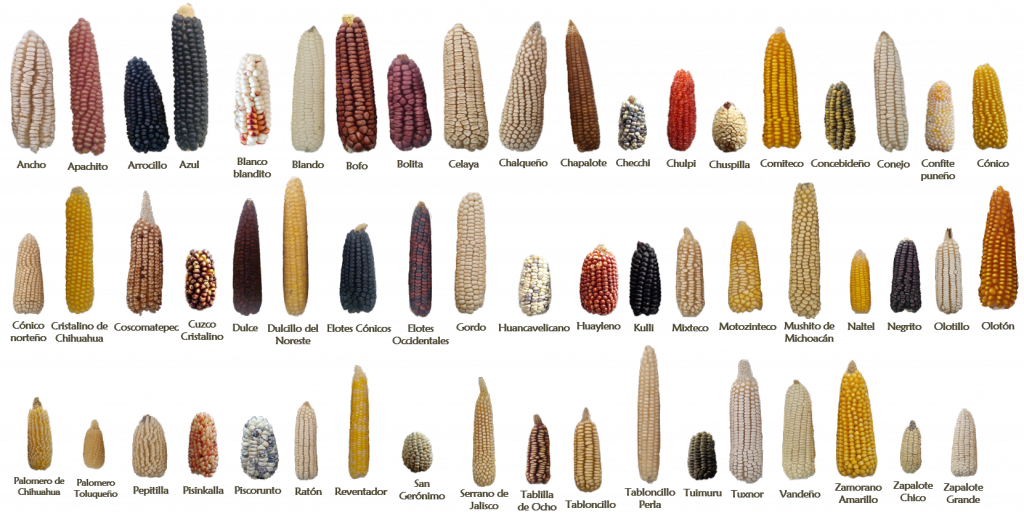

The high level of maize diversity in Mexico is due to its varied geography and culture. As farmers selected the best maize for their specific environments and uses, maize diverged into distinct races, according to Costich. At present there are 59 unique Mexican landraces recorded.

Ancient maize farmers noticed not all plants were the same. Some grew larger than others, some kernels tasted better or were easier to grind. By saving and sowing seeds from plants with desirable characteristics, they influenced maize evolution. Landraces are also adapted to different environmental conditions such as different soils, temperature, altitude and water conditions.

“Selection for better taste and texture, ease of preparation, specific colors, and ceremonial uses all played a role in the evolution of different landraces,” said Costich. “Maize’s genetic diversity is unique and must be protected in order to ensure the survival of the species and allow for breeding better varieties to face changing environments across the world.”

“Organisms cannot evolve if there is no genetic, heritable variation for natural selection to work with. Likewise, breeders cannot make any progress in selecting the best crop varieties, if there is no diversity for them to work with,” she said.

Willcox agrees maize diversity needs to be protected. “This goes beyond food; reduced diversity takes away a part of civilization’s identity and traditions. Traditional landraces are the backbone of rural farming in Mexico, and a source of tradition in cooking and ceremonies as well as being an economic driver through tourism. They need to be preserved,” she said.

CIMMYT/Xochiquetzal Fonseca

Mexican collection preserves maize diversity

CIMMYT’s precursor, the Office of Special Studies funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, aided in the preservation of Mexican landraces in the 1940s, when it began a maize germplasm collection in a project with the Mexican government. By 1947, the collection contained 2,000 accessions. In a bid to organize them, scientists led by Mario Gutiérrez and Efraim Hernández Xolocotzi drew a chalk outline of Mexico and began to lay down ears of maize based on their collection sites. What emerged was a range of patterns between the races of maize. This breakthrough allowed the team of scientists to codify races of maize for the first time.

Today, CIMMYT’s Maize Germplasm Bankcontains over 28,000 unique collections of maize seed and related species from 88 countries.

“These collections represent and safeguard the genetic diversity of unique native varieties and wild relatives and are held in long-term storage,” said Costich. “The collections are studied by CIMMYT and used as a source of diversity to breed for traits such as heat and drought tolerance and resistance to diseases and pests, and to improve grain yield and grain quality.”

CIMMYT’s germplasm is freely shared with scientists and research and development institutions to support maize evolution and ensure food security worldwide.

Willcox said on-farm breeding by Mexican farmers also continues and preserves maize diversity and the culinary and cultural traditions surrounding maize are the reason there is such a wealth of landraces in existence today.

“The diversity preserved in farmers’ fields is complementary to the CIMMYT germplasm bank collection because these populations represent larger population sizes and diversity than can be contained in a germplasm bank and are subjected to continuous selection under changing climatic conditions,” she added.